Getting back to work after a prolonged break is rarely easy. But stories of women and men who went through this transition can teach us how to better navigate a way back in.

Authors of this article: Antoine Tirard is a talent management advisor and the founder of NexTalent. He is the former head of talent management of Novartis and LVMH. Claire Harbour helps people tackle massive challenges of transformation, and to escape the chains of other people's expectations, leading to joyful, inspiring, impactful life and work.

Together they wrote a book and created an online course to support you in becoming more agile in your career, a veritable career acrobat!

It is 2016, and women defiantly burnt their bras in the struggle for equality more than fifty years ago. And yet, ninety five per cent of executives who take a career break for child- raising or family caring are still women. This galling fact was presented to us by Julianne Miles, co-founder of a revolutionary firm called Women Returners, which, as its name suggests, exists to reduce the risks for both the individual and the organisation, in orchestrating a return to the workplace after a prolonged break. Even more saddening is the fact that return to work is typically extremely difficult, for a variety of reasons which we explore in this article. The stories we tell range from dismal to inspirational, of both women and men, and definitely should serve to stimulate us all to greater and better action in this tough, but common navigation, with not many pots of gold at the end of the rainbow.

We start with Barbara, who has recently undertaken what she calls her “fourth transition”, very confidently, having become an expert over the years in reflecting on what changes of context are appropriate for her at any given moment. Having dropped out of university, with literally no idea of what she wanted to do, she entered the advertising industry via the secretarial route, and fought hard to climb up. She worked for a few years in a variety of independent agencies, progressing in various account management roles, and then decided to pursue an MBA degree. During a lecture on intangible assets, she had an “aha!” moment, concluding that the next big business issue would be people, so she signed up for the HR route.

Having returned to the advertising industry and moved effectively up the HR ladder, she then slipped out of the fast lane while taking a calculated break to raise her two growing children. She had returned each time after giving birth, and juggled a mix of full-time and part-time roles, refusing to step down a level in compromise, but was finding this increasingly difficult. When the children reached age 6 and 8, she felt they needed more support from at least one of their parents, so she took a total break from her role. The plan was to take five years, until they were both in secondary school, while doing constructive things around her parenting, like local volunteer work and a doctorate. But she found that she did not really want to go back to the corporate world. This carefully considered choice was facilitated by financial comfort and stability, as her husband was the major bread- winner.

I Can See Clearly Now

While Barbara was clear about what she did not want to do (like big corporates or work in HR for SME’s), it took her about a year to identify what she did want to spend the rest of her working life doing. Her passion for people and HR had not disappeared, however, her slightly “north of fifty” age did not help, and she did not wish to play the old corporate games any longer.

Having established that setting up on her own was the best option, Barbara, whose thinking was facilitated by Women Returners, finally identified a clear niche business opportunity, in the home decoration area, despite not having, as she puts it, “a craft bone in my body”. The Doubleknot Company, which hand makes blankets, has been in existence for just over a year, with promising repeat and multiple purchases giving Barbara a sense she has made the right decision. Though, as she says, “I am old enough, nevertheless, to know that there will be bobbing and weaving involved to maintain the success and the growth”.

Though she did grieve her old corporate life for some time, especially the companionship, the brainstorming, the resources and the professional identity, that mourning is over, as she relishes the freedom and flexibility. She recognises that family support, both mentally and financially, have been crucial in this transition. When asked what advice she would give, she refers to a need for comfort with ambiguity and a flexible attitude. “Use those flexibility skills in combination with a plan”, she recommends.

She believes that resilience and tenacity are key to surviving the juggling act of working parents, and that young people should be encouraged to acquire resilience early, whether through sport or other activities that require sustained effort and commitment. The pressure to manage transition comes quickly in most careers these days. Barbara adapted successfully multiple times, demonstrating to us all that even the most apparently challenging transitions are possible with a large dose of resilience.

Jenna’s story is rather less encouraging, though she is far from unhappy. The transitions she has made in and out of the law profession are actually rather impressive, and her story is possibly more one of a missed calling elsewhere, combined with exceptionally tough non- controllable events.

A brilliant scholar at Cambridge, Jenna graduated in Natural Sciences, with a passion for numbers and analysis, but prepared for a career in Law. After training, she worked in structured finance in an investment bank and did extremely well being lucky to be in the boom of the early nineties. But when her first daughter was born, she had just changed company, and had no rights accrued to maternity leave or a proper return. This started a pattern of what might be called “odds stacked against her”.

As a result of these constraints, Jenna returned to work very rapidly after the birth, though this situation was shortly to be interrupted by her tax lawyer husband’s move to partnership, which meant that they moved house, thus causing her to leave the job to which she had only just returned.

A brief period spent in her husband’s firm helped her to get her CV current again, after the two-year break she had experienced, and this allowed her to move to another firm where the hours were unbearably long. At the same time, her husband’s job under threat, and his health was at risk, with the possibility of a brain tumour. In the end, it was Jenna’s own health that posed even more of a problem, and she in fact suffered a heart attack, aged less than forty!

While convalescing and taking stock, she did some more teaching and then wanted to return to the legal world, which proved to be a far greater challenge than she had expected. The recession had dug in, and she had built up a significant amount of time away from her high- flier role. She was now perceived by the headhunters as out of date and redundant. She was looking for a part-time role, and they told her was that this was impossible.

Take A Chance On Me

Having given up on help from headhunters, Jenna injected some common sense into the situation, and started by contacting the law firms closest to her home. To her amazement, she found that the very first one she asked was happy to talk, and they did work out a comfortable arrangement, that meant she worked four days per week, in school term time only.

However, despite the wonderful return in ideal circumstances, Jenna’s bliss was not to last long, as her second daughter fell very ill, and needed to have proper care from her mother. At this point, Jenna left the law firm and has never returned to formal employment. She does manage a real estate portfolio and has been on non-executive boards of various kinds, so her brain is not idle, but she, too, believes she has become unemployable.

She dreams of returning to academia and of doing a Maths PhD, and one senses that she is really more cut out for that approach to work than the City rat-race. Having total

financial security, she points out that she lives in a road of multi-million dollar houses, occupied by highly educated, highly competent women, who no longer work. Jenna still finds fulfillment in teaching a local boy who has dropped out of school, and in supporting others in her community, but her ennui and search for the next part of the “continuum” she describes are palpable. Did her earlier juggling and remarkable instinct for survival kill the instinct to continue? She herself says “I have never made ‘head’ of anything, indeed, I sometimes wonder if I am just a quitter”. And yet, is it really Jenna who has a lack of grit? Or is it the system that makes it so hard to effect a comfortable return?

Argyro is someone who has known work for a very long time, having started her career at the age of 17, due to family constraints. She paid her way through university and found her first job in a French retail company thanks to her early experience in the tourism business in her native Greece. After an initial stint in customer services, she moved into sales and purchasing, finishing up as European Purchasing Coordinator in Geneva. During this time she saved hard to do an MBA, and on graduation from INSEAD, “ended up more or less by accident” at McKinsey in their London office. At the same time as this, she met her future husband, a Greek entrepreneur.

While she loved the challenging assignments at McKinsey, Argyro decided to return to her home country and found a role organizing the retail division of the Athens International Airport, in the build-up to the Olympic Games. From this came an invitation to help one of the Airport “tenants” to build stores and brands, and so she entered the world of luxury, as General Manager of their Greek subsidiary, which she thoroughly enjoyed.

As she discovered she was pregnant with her first child, Argyro started to see very strong signals that her company was going to be acquired. Her reluctance to be in the post-merger structure, as well as a recognition that she did not want to sacrifice time with her baby led her to part ways amicably with her company, but she was not planning a long break.

You Keep Me Hangin’ On

However, another pregnancy prolonged the gap, and this was the first time since she was seventeen that Argyro was able to take stock, and she asked herself a few “serious questions”. She wondered if she had the opportunity for a “second career”. Should it be about joy? Passion? Expertise? Sustainable for a later stage of life? This reflection showed her that what she most enjoyed was people: “creating beautiful teams of talented people and helping them grow”. So, she went to do a second degree, this time in Strategy and HR Management, while still pregnant with the second.

After a failed attempt to return to work after baby number 2, Argyro managed to get back after number 3, once she had realised that she needed to use her experience as a consultant as the lever. Although she was aiming for a line HR role, it was now obvious that being an HR consultant first was the route to take. This she got, and spent one year happily developing her abilities, after which she was called by a London based multinational Spirits & Beverage company, to work as HR Director, Greece. From this role she developed fast to European roles of increasing seniority, and finally left when it was no longer possible to add strategic value from Athens, when the roles she was suited to were in London.

Argyro now occupies a key strategic and global role in one of the largest companies in Greece, and has apparently got things well figured out. She talks of the importance of knowing her own limits, and working constructively with them. She also mentions that she “chooses” to work with nice people: “we all have families, so it is engrained that we all encourage a healthy balance”. She and her colleagues measure her performance by what she accomplishes and not by how she organizes her day to accommodate work and family commitments. She points to an increase in maturity of attitude in this regard, at least in her environment.

Reflecting on her career and life journey, Argyro tells us how clear it was to her that her husband’s support had been crucial. She describes him as a generous supporter, who welcomes her growth and is proud of it. He is a very participative parent, and things are equitable between them. They work as a partnership, and balance and development are a priority for both of them.

Tim also made a choice to value parenting over corporate life, though in a very different way and order than that used by Argyro. After a classic, successful and travel-heavy start in FMCG marketing, moving from single brand/single country to increasingly senior roles mostly across Europe, his situation was comfortable, with a wife and young family in tow. He was often away on business and worked late in the evening, but this was nothing unusual at P&G. His wife was also carving out a career in the same company, but they somehow juggled as best they could all the different travel, deadlines, and the raising of their two children.

My Heart Belongs To Daddy

Questions had started arising in Tim’s mind about whether the balance was quite right, but the house of cards was not tumbling down yet, so he persisted. Until one evening, he came home from a long business trip to Africa, to find a little note on his bed from his nine-year- old daughter, asking that he attend a “meeting” with her ASAP. The next day, she explained: “Daddy, how can I love you if I never see you?”. Tim resigned only ten days after this bombshell, fortunately in the knowledge that his wife had been offered an opportunity to take a role in the European HQ of P&G. As he and his wife worked through the aftermath, they recognised many other shocking aspects, such as the fact that their younger daughter’s language was increasingly dominated by Tagalog – the language of their wonderful Filipina nanny!

Tim says he does not judge those who do not hear or heed such wake-up calls, but he does not pretend either that the change was easy. Moving to Geneva in itself was not a big challenge, but his new role as full-time father took more getting used to. He missed a similar list of routine and having plans, and experienced a certain amount of emptiness and guilt, both at what he had caused, and what he had given up.

Unlike other “stay at home fathers”, Tim threw himself very actively into a variety of tasks, including doing the school run morning and afternoon, socialising and building constructive relationships with other school parents – almost exclusively mothers. There was no problem whatever in his being accepted into the group, despite his obvious difference. And when, after a year, he found himself able to say “my name is Tim and I am a stay at home dad”, he knew he had “made it”!

While Tim was occupied with several other projects at the time, such as a role in a small start-up and designing and building a house, he describes his role of father as a 90% occupation of his time. As his daughters grew bigger, his involvement with the school grew too and Tim’s question became : “can I mix the important parts of being a dad with the world of work?”.

When, by serendipity, he was contacted by a consultancy firm, he took on a project, which led to another, and now he is helping them to develop their business. This is facilitated by a very actively present grandmother, who supports and helps out willingly.

On the subject of the future, Tim is open and relaxed. For now, he sees the win-win of combining all the good parts of work with the emotional parts of being a father. He remains open to reverting to father at work/mother at home, if that ever feels appropriate again. He is actively modelling his approach in his workplace, repeating often that “he does not want this to get in the way of his being a dad”. As he puts it, this role has become a necessary part of “being me”, though I find a way to ensure the client always comes first. This is achieved by being in the office early and working creatively from home and office to get things done appropriately.

When quizzed on how this works out for the couple, he is unequivocal : it only works if the two are perfectly aligned, and is helped tremendously if there is capital already saved so as to avoid a drastic drop in lifestyle. As he says “nobody is deprived, but we do control our spending in a way we would not have done a few years ago”. He recognises that the feelings of guilt and discomfort at the outset were inevitable and the reflection of a substantial change, but that they have been more than compensated for by the positive change in the family as a result.

The final big advantage to which Tim refers, as a result of his choices, is that of having become a better decision-maker. He says he is much better at identifying and setting priorities, and bringing the right mix of emotion and practicality to any choice he faces these days.

We can be much in admiration of Tim and his family for taking this brave choice, but should recognise that it is ‘exceptional’ only because he is a man. The kinds of challenges he describes are no different to those undergone by countless mothers, apart from the fact that he is a man, not a woman – an interesting point to ponder.

Mui Gek, a Singaporean, fell into the shopping centre business rather by accident. She spent a few early years as a civil engineer before being referred by a friend to a leasing role in the years that Raffles City shopping centre was being renovated and repositioned. She excelled in this role, becoming adept at tenant mix planning, business plan analysis and tough negotiation. She was soon snapped up by giant Hongkong Land, when they were entering the Singapore market with a new mall to open. Her reputation and her speedy learning came into play and her success was once again resounding. When the mall opened, she was given increased responsibility for marketing and tenant relationships management.

Ain't No Mountain High Enough

In the meantime, Mui Gek had married a Frenchman, and they decided to move ‘back’ to France, landing in a provincial city just after 9/11. She aimed to use her experience to enter the French luxury goods industry and so started out by learning the language and did an MBA in a local business school. From here on, the story becomes one of grit and determination, as it was a mammoth task for Mui Gek to find a job in a tough French market as a visibly and audibly very foreign person in a provincial French city.

She created, from scratch, an extensive network from her immediate friends, MBA teachers and family. This networking exercise landed her her first job in France where she started by working in a family business with a large project to go and explore the Chinese market for shopping centres. On her return from China, with the news that it was not the right time for the investment, her employers encouraged her to stay for a while longer. Mui Gek wasted no time in learning new skills and the breath of ability she was developing was to serve her soon in another challenging search.

While pregnant with her first child, Mui Gek and her husband decided that she would take a break to have the baby and to figure out her next move. However, less than two years later, they found themselves with a toddler and new-born twins! While changing the 600 plus diapers per month, Mui Gek was happy to become a mother and was well supported by her husband, though she admits she had not been instinctively a maternal type. But when the twins were coming up to two, she started to raise her head once more, and to feel it could be interesting to return to work.

Yet again, networking skills came to the fore and she really worked her little black book harder than ever before. This time, it led to an introduction to none other than Antoine, the co-author of this article, who was at the time recently appointed as head of talent at LVMH. Mui Gek’s mix of skills was unusual to say the least, and not one that neatly fitted any particular vacant job in the luxury group. Her difference was that beyond her obvious real estate and retail experience, she had doggedly stayed up to date on workplace issues, on fashion, luxury and more.

Her conversations with LVMH had been pleasant but not fruitful. In the meantime, her husband’s work was moving geography and they were planning a move to Brussels. But shortly before the move, she received a call from LVMH, offering her a perfect job, using all her skills. The couple realised it was an opportunity not to be refused, as her husband Olivier said:” If you don’t seize this opportunity, you will never work again”.

Her demonstration of consistent learning was the clincher. This new role was created specially for her. LVMH felt they needed this mix, given that their real estate strategy was inharmonious, an an expert hand with negotiation and diplomacy skills could be a great asset. She was, as she says, “the right person at the right time”. She disproved the naysayers, getting past her language and accent problems, networking furiously to make friends and allies all over, and using her unique blend of knowledge, passion and persuasion to bring them on board. As a result, not only has she created a hitherto unheard of collaboration between previously hostile, competitive brands, she has been offered increasingly interesting and developmental roles, which she handles with confidence, disarming more than one senior executive, and somehow charming them with her frank and very different style. Mui Gek hopes to continue to create options for herself and the company, while keeping balance at home.

Our stories in this article are perhaps more similar than usual, and this may well be significant. While we have attempted to show a range, we have nevertheless not related any total shipwrecks, and of these, we know, there are many. We see individuals who have been supported by family, and comfortable finances, however difficult this balancing act may have been. These individuals find creative solutions to the challenges that not everybody manages, but the challenges do not go away. There are also countless individuals who are not so lucky with their family situation. The balance is a lot less easy to find if you are on your own and there is no friendly grandma down the road –- a reality faced by millions. We are delighted to tell hopeful stories of those who have found their balance, but we are reasonably sure that there may just simply not be a holy grail, when it comes to “having it all”.

Getting Better

Emerging initiatives from corporations to help professionals return back to work also give a ray of hope. Financial institutions and professional service firms have woken up to the attractive qualities of a pool of talent that they have overlooked. In an effort to access scarce skills, a growing number of these organisations have introduced ‘returnship programmes’ to provide a bridge back to work for high calibre women (or men) who want to return to corporate life and find their way blocked by a gap on their CV. Goldman Sachs first coined the phrase “returnship” in 2008 to describe its 10-week paid programme to reintegrate people – usually mothers – after extended career breaks. This innovative route back to work reached the UK in 2014 and many other financial institutions followed internationally including Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, RBS, J.P. Morgan and Lloyds Bank. Is there any evidence of success of these returnship programmes? There is longer term data from Goldman Sachs in the US who have consistently taken on half of their returnship participants into permanent positions. More recent data on UK returnship programmes suggest that retention rates may be even higher. Interestingly, those who have found permanent jobs have subsequently sparked discussions with their employers about more flexible forms of working. This has prompted banks to think about their returners before they have even left. According to research by the consultancy Women Returner, the overall number of programmes in the UK tripled, increasing from three in 2014 (all in banking) to nine in 2015 (with five in banking). Evidently, these schemes are proving popular and transformational and should spread across countries and industries in the future.

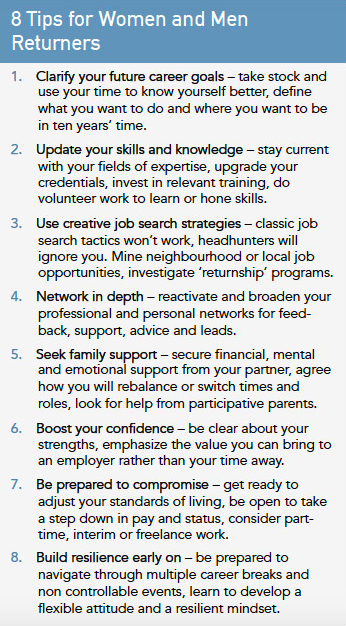

There is much learning – and much to be done: both for corporations who could undoubtedly make these returns easier, and for the returners themselves, who must battle history, tradition and practical reality with courage every single day.

Career Intelligence

Resources

Copyright © 2026-2021 Network Capital