The first time I had a long conversation with Professor Pratap Bhanu Mehta was at the Harvard India Conference in Boston in 2019. We were both speakers there. More precisely, he was the keynote speaker and I was speaking at a few panels on education and reskilling. Despite his busy schedule, he met me and a bunch of other alums for breakfast. Our conversation revolved around institution building, culture of Ashoka and new initiatives at the university. What struck me most was the way he explained liberal arts education.

Liberalism and Liberal Arts Education

“Liberalism” and “Liberal Arts” are often misunderstood. Liberalism means protecting and enhancing the freedom of the individual to be the central problem of politics. Confusing liberalism with being leftist or rightist is incorrect and nothing more than an intellectual shortcut.

Liberal arts education offers an expansive intellectual grounding in all kinds of humanistic inquiry.

By exploring issues, ideas and methods across the humanities and the arts, and the natural and social sciences, liberal arts students learn to read critically, write cogently and think broadly. A liberal arts education challenges you to consider not only how to solve problems, but also trains you to ask which problems to solve and why, preparing you for positions of leadership and a life of service. That is why most top universities in US and Europe provide a liberal arts education to all undergraduates, including those who major in engineering.

This is something India should strongly consider and I am glad that the National Education Policy aims to strengthen the liberal arts ecosystem in the country.

Liberal Arts and I

One of the best professional decisions I took in my early twenties was to invest a year studying liberal arts at Ashoka University. I was part of the first cohort of Young India Fellowship where 57 of us learned the art of connecting ideas from different walks of life. Studying anthropology, philosophy, history, literature, art and economics after a couple of years of work experience helped me understand what I wanted to do and why.

I got a chance to learn from top social scientists, distinguished business leaders, award-winning authors, philosophers and economists, both free market proponents and those who advocated for a stronger role of the state. The founders were closely involved with us spending countless hours with us in the form of guest sessions, mentoring chats and debates on a wide range of subjects.

The best way to understand something is to know the opposing argument better than your own. I learned this at Ashoka.

I find it amusing when people say that Ashoka is trying to indoctrinate its students. If you can be indoctrinated so easily, you never really understood liberal arts education. Further, how gullible do you think Ashoka students are? We often disagree, think on our own, make up our own minds and perfectly fit the “Argumentative Indian” tag.

The whole premise of such an education is to empower you to question and critique. I think it is obvious but let me be clear that critique is not criticism, and criticism isn’t such a bad thing. Constructive criticism is the foundation of personal, professional and societal growth.

Professor Pratap Bhanu Mehta offers some of the smartest critiques in the country. Sometimes I find myself disagreeing with him but I listen to/read what he has to say nonetheless. Agreeing and disagreeing with him has made me smarter.

Liberal arts education does not thrive when the goal is consensus. Surrounding ourselves with those who think, act, write and vote like us is a recipe for disaster. It is the source of all cognitive biases and results in catastrophic decision making.

In my Ashoka cohort, there were fellows from all political, social and economic convictions. Learning with them, agreeing to disagree with them, negotiating with them, understanding the hidden contours of Indian thought made me who I am.

Professor Mehta’s Departure

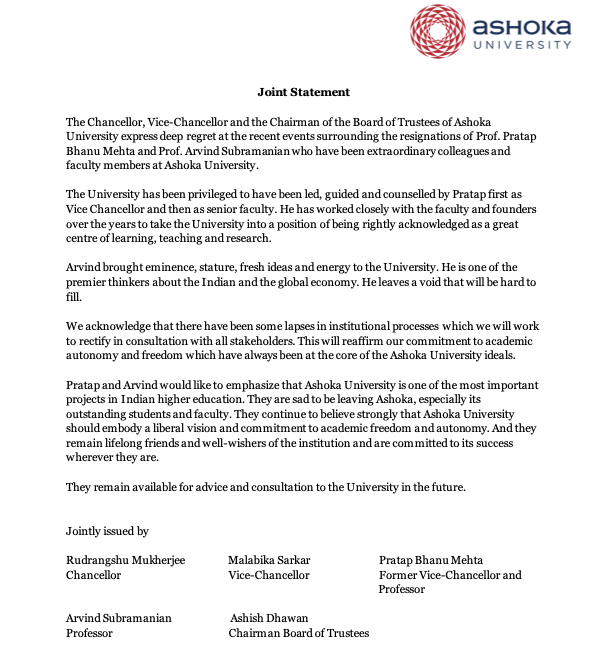

Few days back I learned that Professor Mehta had resigned from Ashoka. Right after him Professor Arvind Subramanian parted ways. Many speculative theories have been advanced in the media so there is no point repeating them. I am attaching the official documents for your perusal.

- Joint Statement issued by Chancellor Rudrangshu Mukherjee, Vice-Chancellor Malabika Sarkar, Former Vice-Chancellor and Professor Pratap Bhanu Mehta, Professor Arvind Subramanian and Chairman of the Board of Trustees Ashish Dhawan

- Letter from Ashish Dhawan

It goes without saying that it came as a rude shock. The Chancellor, Vice-Chancellor (V-C), and the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of Ashoka University Sunday expressed “deep regret” at the recent events surrounding the resignations of scholar and acknowledged “lapses in institutional processes”.

Lapses are unfortunate but they happen to be great teachers. At the heart of it, Ashoka is an experiment in higher education and the first rule of experimentation is to be prepared for failures, even ones that question your own existence. If you cease to experiment for the fear of failure, you won’t last. If you don’t learn from your experiments, you won’t last either.

Ashoka is arguably one of the most interesting experiments in the higher education space.

When I speak to my friends and professors at INSEAD, Oxford and Wharton, I am struck by what they have to say about the university. Some of them have come forward to criticize the recent events. They have great expectations from Ashoka. If they feel believe Ashoka made errors, their criticism needs to be considered.

Ashoka is trying to change the way students learn and think. Changing systems and building institutions takes generations. Ashoka is all of 7 years old. Professor Mehta’s departure won’t be the first or the last challenge it will face. How it reacts to this existential challenge and what it learns from it will determine its future.

Ashoka is trying to change the way students learn and think. Changing systems and building institutions takes generations. Ashoka is all of 7 years old. Professor Mehta’s departure won’t be the first or the last challenge it will face. How it reacts to this existential challenge and what it learns from it will determine its future.

Pain + Reflection = Progress

Pain is something we all try to avoid but if we want to learn from setbacks, we need to change our relationship with pain – personal, societal and institutional. Ray Dalio, the longtime leader of Bridgewater, the largest hedge fund in the world, argues that pain “is a signal that you need to find solutions so you can progress.”

Only by understanding it and reflecting on it can we start to learn and evolve.

“After seeing how much more effective it is to face the painful realities that are caused by your problems, mistakes, and weaknesses, I believe you won’t want to operate any other way,” Dalio writes in his book Principles.

Dalio’s mantra is Pain + Reflection = Progress

For Ashoka to embark upon a new phase of institutional progress, it needs to reflect deeply on the pain of losing two star faculty members and complement it with serious reflection among founders, faculty members, students, alumni and other key stakeholders.

This won’t be an easy process. Many uncomfortable questions are likely to come up. Being defensive, pointing fingers, calling for resignations are suboptimal ways to go about it. More than demonstrating outrage or anguish, we need to understand what led to such a situation and what can be done to prevent it in future.

What gives me hope is the integrity of the founders many of who I have gotten to know closely over many years, the commitment of faculty to ensure Ashoka is a safe space for all voices and the liberal arts foundation of the students and alumni of Ashoka who are trained well to ask difficult questions while keeping an open mind to possible resolutions.

Has Ashoka done everything well? Could it do more to include all voices and develop stronger systems and processes? Absolutely. It must. We live in a time where we love to make heroes and villains at the drop of a hat. There is no point resting on your laurels or using perfection as an excuse for progress.

Ashoka has made several mistakes, just like any other institution or organization trying to find its feet. It should own up to them and commit to making quality liberal arts education to as many people as possible.

Anti-Fragile Ashoka

I got introduced to Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s while writing my book “The Seductive Illusion of Hard Work”. He taught me the concept of anti-fragility: systems and institutions that strengthen through chaos.

In the 21st century, resilience is not enough. Surviving one shock or one crisis does not mean that we will be ready for the next one.

We will need to make shocks and backlashes our teachers and learn from them. We will need to become stronger through chaos and crises. I think Ashoka has gone through a major existential crisis but I have firm belief that it will emerge stronger from it. Ashoka must strive to become more anti-fragile in the years to come.

No one person or set of people own Ashoka. We are all building it together in our own small ways. We are sure to tumble and fumble but commit to becoming stronger each time.

Professor Mehta in his parting letter said, “This episode will be seen to have hurt Ashoka’s reputation. But in a larger sense Ashoka’s reputation will be enhanced, not by what the University did but what you did. You may lose a couple of Professors. But anyone looking at you will wonder in admiration. The poise and articulacy with which your defended important values and demanded accountability should make anyone want to associate with this university. You are its beating heart and soul and nothing can damage that.”

As one beating heart and soul of this iconic institution, I commit to doing my bit. You should too, even if you are not an alum of Ashoka. Democratizing liberal arts education is a national priority and all of us need to weigh in. May a thousand Ashokas blossom to raise awareness and inspire sharp critique of some of the most urgent national and international questions.

Join our newsletter

Get updates on new masterclasses, fellowships, podcasts & more.

Thank you!

Career Intelligence

Resources

Copyright © 2026-2021 Network Capital